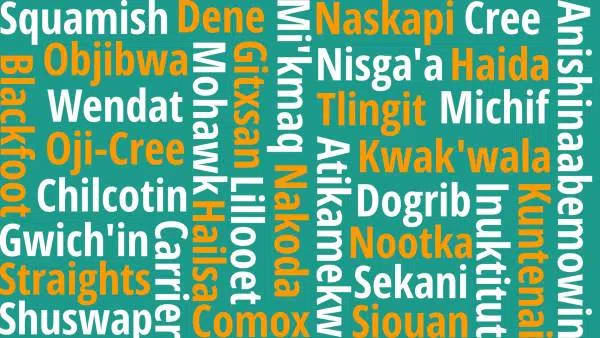

March 31st is Indigenous Languages Day !

The Windspeaker Radio Netowrk is proud to being DAILY Indigenous Language Programming across the entire province of Alberta and throught the world , online.

You can tune in to various language programs to learn Dene Suline, Nêhiyawêwin (Cree) , Blackfoot , Michif, Stoney and Stoney Nakota. All Indigenous languages spoken in Alberta.

In recent decades, the revitalization of Indigenous languages has been identified as a human right, and the Canadian government has received Calls to Action to rectify the colonial harms caused to Indigenous languages. This fact sheet gives you current information about Indigenous languages in Canada and a list of ways in which you can help revive them.

The importance of Indigenous languages for Indigenous people—and all Canadians :

The importance of Indigenous languages for Indigenous people —and all Canadians The identities, lives and futures of Indigenous peoples have been immeasurably affected by the forced removal of their languages. The efforts they are making to bring the languages back to life can have a huge, positive impact on individuals, families and communities. Indigenous languages are also part of the shared history and national heritage of all Canadians. They hold the keys to irreplaceable, intelligent worldviews and intimate understandings about the environment, intergenerational education and Canada’s history. Our lands and species depend on these languages. They hold priceless insights into interspecies symbiosis.

Key facts about Indigenous languages in Canada:

At present, 96 per cent of the world’s approximately 6,700 languages are spoken by only 3 per cent of the world’s population.

Although indigenous peoples make up less than 6% of the global population, they speak more than 4,000 of the world’s languages.

Conservative estimates suggest that more than half of the world’s languages will become extinct by 2100.

Other calculations predict that up to 95 per cent of the world’s languages may become extinct or seriously endangered by the end of this century. The majority of the languages that are under threat are indigenous languages.

It is estimated that one indigenous language dies every two weeks.

Indigenous languages are not only methods of communication, but also extensive and complex systems of knowledge that have developed over millennia. They are central to the identity of indigenous peoples, the preservation of their cultures, worldviews and visions and an expression of self-determination.

When indigenous languages are under threat, so too are indigenous peoples themselves.

The threat is the direct consequence of colonialism and colonial practices that resulted in the decimation bof indigenous peoples, their cultures and languages. Through policies of assimilation, dispossession of lands, discriminatory laws and actions, indigenous languages in all regions face the threat of extinction.

This is further exacerbated by globalization and the rise of a small number of culturally dominant languages. Increasingly, languages are no longer transmitted by parents to their children.

Indigenous language proficiency tends to be higher (44.9%) among those living in reserve communities compared with those living off reserve (13.4%). Living in an area with a high concentration of speakers may support language acquisition and use. Yet more than half of Indigenous people now live in urban areas of 30,000 or more. This means language support is needed everywhere in Canada, not only in onreserve communities. For Indigenous people who speak or are learning an Indigenous language as a second language.

National and International Support for Indigenous Languages and Cultures The Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

To address the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission put forth 94 Calls to Action. Of these, six are specific to language and culture. They range from asking the federal government to acknowledge that Aboriginal rights include Aboriginal language rights to calling upon post-secondary institutions to create university and college degree and diploma programs in Aboriginal languages.

Want to help? Try these ideas:

1. Learn the name of your town or city

in the Indigenous language(s) of

the region.

2. Learn a greeting—and a response!—in the Indigenous language of your region and use it often.

3. Incorporate Indigenous place names and greetings on posters and signs at your workplace.

4. Introduce the local Indigenous language(s) to your family, in your home and in your place of work. You can use resources like FirstVoices (www.firstvoices.com) or smartphone language apps. Try labelling household items in the local Indigenous language(s) as a fun learning aid, or purchase duallanguage children’s books.

5.Push to rename streets and regions with Indigenous names and signage in consultation with local Indigenous language experts.

6. Recognize Indigenous languages as living languages by identifying them in land acknowledgements. (For example, say: “Today, we are meeting on W̱SÁNEĆ land, the ancestral and unceded territory of SENĆOŦENspeaking people” or “We are gathered on the territories of the W̱SÁNEĆ people. The language Indigenous to this land is SENĆOŦEN.”)

7. Advocate for Indigenous-led and regionally-relevant language instruction in schools for all Canadian children. 8. Publicly support and lobby for immersion programs run by Indigenous language groups across Canada from preschool to post-secondary.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

A number of articles in UNDRIP pertain to Indigenous languages. For example, Article 13 states that: 1. Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places and persons. 2. States shall take effective measures to ensure that this right is protected and also to ensure that Indigenous peoples can understand and be understood in political, legal and administrative proceedings, where necessary through the provision of interpretation or by other appropriate means.

Information from :

Dr. Onowa McIvor

Associate Professor and Co-lead,

NEȾOLṈEW̱ SSHRC Partnership Grant

Department of Indigenous Education at

University of Victoria

and

The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

Comments